The code of Gentoos Law was the first initial attempt in British India to prepare ancient Indian law. It was about the culture and local laws of various parts of Indian subcontinent. It also explained the Hindu law of inheritance (Manusmriti). The Pandits and the Maulvis were associated with judges to understand the civil law of Hindus and Muslims.In the early 16th century, Gentoo was a term commonly used to distinguish between the local religious groups in India from the Indian Jews and Muslims. The Oxford English Dictionary defines Gentoo as ‘a pagan inhabitant of Hindustan, a heathen, as distinguished from Mohammedan’. Till about the 18th century, the native population of India (other than Jews and Muslims) were labelled by the Europeans as Gentoos. That is the reason why the first digest of the Indian legislation drafted by the British in 1776 for the purpose of administering justice and to adjudicate over civil disputes among the people of India belonging to local religious groups was titled as ‘A Code of Gentoo Law’.

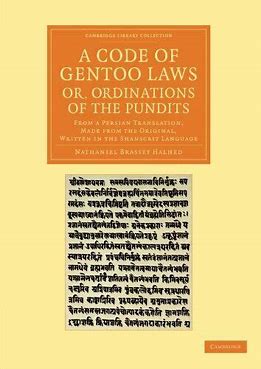

The Gentoo Code is a legal code translated from Sanskrit into Persian by Brahmin scholars, and then from Persian into English by Nathaniel Brassey Halhed, a British grammarian working for the East India Company. It was printed privately by the East India Company in London in 1776 under the title A Code of Gentoo Laws or, Ordinations of the Pundits. The translation of Hindu laws were funded and encouraged by Warren Hastings as a method of consolidating company control on the Indian subcontinent. In 1777 a pirate edition of Gentoos law was printed; and in 1781 a second edition appeared. Translations into French and German were published in 1778. There was a fast growth seen in the British colonial environment and the rise of the East India Company, the British courts in India had to adjudicate on increasing number of legal disputes among the locals. The Court of Directors of the East India Company decided to take over the administration of civil justice and felt that it would help its business interests if it could involve in ‘Hindu learning’ to decide upon civil matters.

Blog by Kushala Simha.