ABSTRACT

The Viksit Bharat- Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, 2025, that replaces the Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005, marks a significant restructuring of India’s rural employment regime. While the Act increases the statutory entitlement to employment to 125 days and retains protective features such as an unemployment allowance and timely wage payments, the normative allocation of funds, continuous Centre-State cost sharing, and an Agricultural Pause are introduced. These structural changes alter the legal character of the right to employment guarantee by rendering it susceptible to fiscal ceilings and temporal suspensions. Through this article, an attempt is made to trace how the new architecture transforms a demand-driven, justiciable right into a regulated developmental entitlement.

KEYWORDS

Rural employment guarantee, VB-G RAM G Act 2025, MGNREGA repeal, normative allocation, agricultural pause, fiscal federalism, justiciability of welfare rights

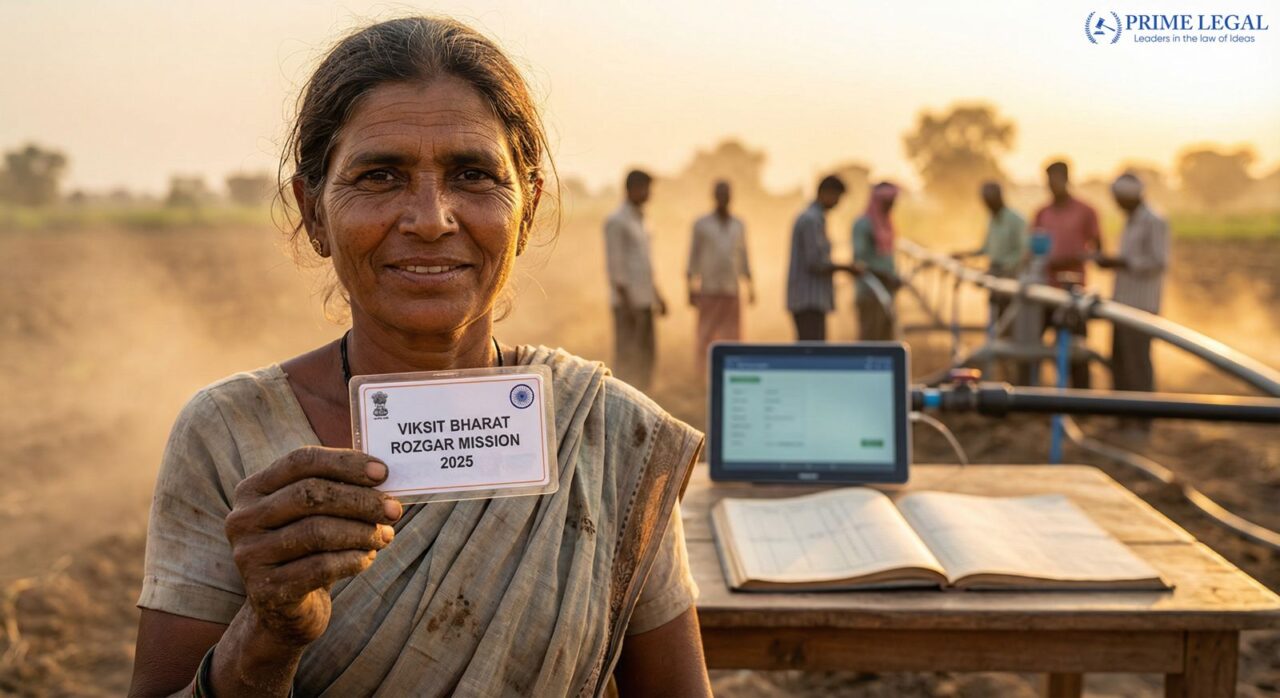

INTRODUCTION TO A LEGISLATIVE MILESTONE

In December 2025, the rural welfare framework in India saw its biggest makeover in two decades with the enactment of the Viksit Bharat- Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, 2025 (VB-G RAM G Act). Given that it received the Presidential Assent on the 21st of December, 2025, this Act thereby nullifies and replaces the “Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, 2005,” also commonly known as “MGNREGA”.

MGNREGA is internationally recognised as a pioneering rights-based social security statute, which lifted employment from a discretion-based welfare measure to an enforceable right. In contrast, the VB-G RAM G Act presents itself as a development-centric law in keeping with the national imperative of securing a “Viksit Bharat” by 2047. The change signifies a conscious and philosophical shift, from an open-ended, demand-driven distress-relief mechanism to a patterned and fiscally calibrated model that seeks to integrate labour welfare with infrastructure development and economic productivity.

EXPANSION OF THE STATUTORY EMPLOYMENT ENTITLEMENT

A key continuity under the new Act is the enhancement of the employment entitlement itself. Section 5(1) of the VB-G RAM G Act uplifts the legislative guarantee of wage employment from 100 days to 125 days in every financial year for each rural household, where members of the household willingly offer unskilled manual work. However, this act took place due to continuous pressure regarding income security in the light of inflation, agrarian distress, and climate change.

The Act provides that if employment is not provided within fifteen days of a valid demand, then the unemployment allowance shall be retained. It also reinforces wage protection by making weekly payments compulsory and, in any case, payment within fourteen days, along with statutory compensation for delays. On paper, these provisions suggest continuity with the rights-based architecture of MGNREGA. However, as subsequent provisions show, the enforceability of this guarantee has been distinctly recalibrated.

NORMATIVE ALLOCATION AND THE RECONFIGURED FINANCIAL ARCHITECTURE

The most basic contrast to the MGNREGA structure comes from the financial structure of the VB-G RAM G Act. The MGNREGA stood out as an open-ended or demand-based system under which the Central Government was bound to disburse funds based on employment demands. The 2025 Act introduces a normative model of funding allocation. Section 4(5) of the law gives the Central Government the authority to fix an annual ceiling of disbursements per state with an independent criterion of poverty. The intent of the reform is to ensure spending predictability for rural employment spending.

It is pertinent to note that the Act neither alleviates the financial burden on the States in the allocation process. In the case of general category States, the total cost, including the cost of materials and the cost of wages, is shared in the ratio of 60:40 between the Centre and the State right from the first rupee of the outlay (90:10 in the case of the North-Eastern and Himalayan States). This is a major shift from the previous regime, wherein the Central Government incurred the entire cost of the wages of the workers.

Once expenditure exceeds the Central Government’s allocation, the entire burden rests on the State Government for extra employment. Consequently, States face a dual obligation: shared fiscal responsibility within the allocation and exclusive liability beyond it. This restructured cost-sharing arrangement substantially increases State-level fiscal exposure and incentivises tighter control over employment demand.

AGRICULTURAL PAUSE AND THE DILUTION OF JUSTICIABILITY

One of the most debated aspects of the VB-G RAM G Act is the carrying out of the “Agricultural Pause” under Section 6. Responding to arguments that public works schemes distort rural labor markets during peak agricultural seasons, the Act confers upon State Governments the right to temporarily suspend works for up to sixty days in a financial year.

The stated purpose is to ensure availability of labour for sowing and harvesting work. The Act formally states that the statutory entitlement of 125 days must be met during the remaining part of the year. But this provision fundamentally changes the character of the employment guarantee.

A justiciable guarantee is one in which the worker is entitled to file a case against the State concerning their employment at any given time. The State will then be compelled to either grant the worker his/her employment, through the court, or pay compensation. Under the new regime, employment cannot be claimed or enforced during a notified pause period. Read in conjunction with the normative allocation scheme, the enforceability of the guarantee is further limited because work cannot be mandated once the assigned funds are spent unless the State is willing to bear the full cost.

Thus, while the Act maintains the form of statutory guarantee, its content is redefined: the right to work is turned from an unconditional right into a regulated benefit under temporal suspensions and fiscal ceilings.

ASSET CREATION AND DEVELOPMENTAL ORIENTATION

The change of name of the scheme to “Mission” now marks a clear shift towards becoming a provider of lasting assets. The wage employment under the Act needs to be brought in line with works that form part of the Viksit Bharat National Rural Infrastructure Stack. The Act focuses on four types of works, namely water conservation, rural connectivity, infrastructure facilitating livelihoods, such as storage and processing facilities, and resilience to climate change.

The planning process under the scheme is tightly integrated with the PM Gati Shakti IT tool. The Gram Panchayat has to prepare “Viksit Gram Panchayat Plans” that are harmoniously integrated at the state and national levels in the infrastructural maps of the country. This indicates that the planning process, unlike in the previous decentralised planning regime, is integrated and productivity-focused in nature.

TECHNOLOGY, TRANSPARENCY, AND GOVERNANCE

The VB-G RAM G Act embeds digital governance into statutory provisions to an unprecedented degree. Biometric attendance, geo-tagging of assets, and AI-based analytics are now mandatory to deal with leakages, duplicate job cards, and financial issues. It has again reemphasized the tenets of MGNREGS’s transparency through legal obligations on “Weekly Disclosure Meetings” in the Gram Panchayat, wherein details of works, muster rolls, and funds released are to be shared through physical and electronic means.

Importantly, the Act has treated the Technological failure as an administrative lapse rather than a worker default. This is towards observing the intent of ensuring that no exclusion happens for connectivity or authentication-related issues. However, apprehensions regarding access, digital literacy, and marginalisation of vulnerable groups remain strong for this technology-intensive regime.

CONCLUSION

The Viksit Bharat- Guarantee for Rozgar and Ajeevika Mission (Gramin) Act, 2025, therefore, marks a decisive recalibration of the rural employment framework of India. Increasing the statutory entitlement to 125 days means that the State has continued to commit itself to the support of rural livelihoods. At the same time, the normative allocations, shared fiscal liability from the outset, and the agricultural pause were marked departures from the unconditional, demand-driven ethos of the MGNREGA.

Rather than an employment guarantee, the Act reconfigures this as a justiciable right into a regulated entitlement set within fiscal discipline and sectoral priorities. Whether this strengthens rural development or undermines labour protection will be a matter of State capacity, fiscal choices, and accountability mechanisms. The VB-G RAM G Act, therefore, is both a successor statute and a redefined social contract between the rural citizen and the Indian State in the quest for a “Viksit Bharat.”

“PRIME LEGAL is a full-service law firm that has won a National Award and has more than 20 years of experience in an array of sectors and practice areas. Prime legal falls into the category of best law firm, best lawyer, best family lawyer, best divorce lawyer, best divorce law firm, best criminal lawyer, best criminal law firm, best consumer lawyer, best civil lawyer.”

WRITTEN BY: USIKA K